Waters Center Blog

It’s a question many of us return to again and again. For the Waters Center, our response to that question has been rooted in systems thinking. Not systems thinking for its own sake, but to support people in making sense of complexity, shifting the systems they are a part of, and uncovering possibilities.

Nearly a decade ago, on a sunny bench in New England, this very question surfaced in a casual conversation between Tracy Benson, former President of the Waters Center, and Jay Forrester, an early pioneer in the field of systems thinking who is often credited as the father of system dynamics (System Dynamics Society, n.d.).Tracy was visiting Jim and Faith Waters, the founders of the Waters Center, then the Waters Foundation. The Waters and Forresters lived in the same community and were friends, so it wasn’t uncommon to bump into Jay during visits.

In a conversation about systems thinking, shared history, and outreach, Jay spoke of a potential tipping point for impact: if systems thinking could reach 10% of the entire world population, it might spark exponential growth—enough to change the world for the better.

At the time, it was just an idea, a passing topic in a much broader conversation. But the phrase lingered, resurfacing over the years in unexpected ways. It came up in conference presentations, in Advanced Facilitator Credential (AFC) sessions, and one day it took on new life during a conversation between Tracy and Kisha Davis-Caldwell, a Waters Center credentialed advanced facilitator.

“We were talking about how many people you need in an organization to be systems thinkers for it to be impactful,” Tracy recalled. “We talked about the power of one, and how one becomes two, then three, then four. Then I remembered what Jay Forrester said about how 10% of the world, or even 10% of an organization, is the tipping point for sustainable impact. And Kisha said, 'That sounds like the title of a book to me, The Road to 10%: How to Transform a System, or How to Transform the World.'”

In 2024, the “Road to 10%” became more than an idea. It became a guiding premise to capture the mission of the Waters Center: how systems thinking can make the world a better place through steady ripples over time, ripples rooted in caring relationships, learning, and adaptability.

As the Waters Center marks 35 years, we’re reflecting on our journey toward our mission. Not just what the Road to 10% means to us, but what it might mean more broadly: for communities, organizations, and people everywhere who are navigating complexity.

How systems thinking can help create a better world

At its core, systems thinking helps us recognize the interconnectedness of everything, from people to policies to the patterns that shape our lives. It invites us to both zoom in and out, ask informed questions, and notice how even small actions can create long-term impacts.

Importantly, it’s not merely a collection of tools or a single solution. It’s a lens, something we bring to how we honor perspectives, recognize moments that matter, and work together to make decisions.

As Tracy explains, “If you truly are a systems thinker, you pay attention to the consequences of what you say and what you do… There's increasing awareness and expectations that things move quickly. And because of that, the speed of thought and action can create a lot of messes. I think that systems thinking can still live and breathe in a quick, fast-paced world, but it requires some intentionality.”

And that kind of intentionality is important. Not just for addressing big challenges, but in our daily conversations and relationships. Systems thinking helps us shift from looking at individual causes to structures and patterns that are creating outcomes. It invites pause and consideration of an issue fully and the opportunity to practice many of the other Habits of a Systems Thinker (the Habits).

Joan Yates, former Senior Vice President of the Waters Center, noted the impact of systems thinking and practicing the Habits: “If everyone could simultaneously see the big picture, surface and test their assumptions, understand where the leverage is... it would allow people to function more compatibly and productively within the systems they live and work in.”

Over the years, we’ve seen how the smallest shift in perspective can change how people engage with complexity. When someone makes their thinking visible and has the space to explore it, they often show up differently. As Sheri Marlin, Executive Director of the Waters Center, shared: “[Systems Thinking] gives people confidence that they can think through and solve a problem, whether it's very close and personal to them or whether it is taking on a bigger change in their community or their nation.”

Walking the Road

The global population is estimated at 8.2 billion people. That means 10%, the tipping point Jay Forrester spoke of, would be 820 million. A lofty goal by any measure. So how do we get there?

We start where we are.

Systems change doesn’t come from one grand solution. It comes from intentional practice. From the structures we build. From the communities we nurture. And, perhaps most of all, from the relationships and networks we invest in over time, across distance, through shared purpose.

And purpose is a critical consideration. Systems thinking provides a powerful lens shaped by the mindset and values of the people applying it. That’s why it is important to not just focus on concepts and tools, but the relationships and reflective practices that help ground systems thinking in purpose and care.

That grounding has guided the Waters Center since the beginning.

Our story began with a conversation between MIT Dean Emeritus Gordon Brown and Catalina Foothills Superintendent Dr. Bob Hetzel. From there, shared applications from Dr. Brown took root in Tucson, Arizona. Middle school students explored system dynamics using classroom sets of computers secured through Apple’s Classrooms of Tomorrow program. Teachers gathered after hours to read The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge. A newly hired principal, Mary Scheetz, a naturally talented systems thinker, insisted on taking a whole-school approach.

What began in a single classroom made its way into new spaces—one conversation, one connection, one insight at a time. The work happening at That School in Tucson caught the attention of systems thinkers like Donella Meadows and Peter Senge. As more people took notice, the ideas began to circulate: first across the district, then around the U.S, and eventually well beyond.

In-person workshops and convenings emerged to meet the moment. Over time, online offerings took shape, evolving into the Thinking Tool Studio. Then came Open Studios, collaborations and consulting, and the Advanced Facilitator Credential. All of it growing out of a desire to support people not just in learning the tools and Habits of a Systems Thinking, but in walking the road to 10% together.

The approach hasn’t changed: stay in relationship, learn what works, and keep adapting with care. In the words of Tracy, it's a, "deep curiosity about what’s really going on with people, not just delivering tools but helping people apply them in a way that feels meaningful."

That curiosity is still at the heart of what makes this work possible, not only in schools or organizations, but in everyday life. When we bring systems thinking into our relationships, our work, and our communities, we create the conditions for connection and change.

An Invitation to Walk

The Road to 10% isn’t just about reaching a number; it is a vision, an invitation. Not always fast. Not always visible. But always moving through connections.

For the Waters Center, 35 years of systems thinking work has taught us that transformation doesn’t happen from the top down or outside in. It happens through people. Through stories. Through practice. When we support each other in seeing systems more clearly and in responding with greater intention, something shifts. And those shifts ripple.

Wherever you are, whether you're deep into your systems thinking journey or taking your first steps, we invite you to walk this road with us.

What’s one small ripple you can make today?

With Gratitude

In writing this piece, as a beneficiary of the Waters Center’s work before joining the team, I had the distinct privilege of interviewing Tracy Benson, Sheri Marlin, and Joan Yates. Their titles appear throughout, but behind them are decades of laying the foundation for this work, building relationships, and sending systems thinking ripples around the globe.

Works Cited

System Dynamics Society. (n.d.). Jay W. Forrester. https://systemdynamics.org/product/principles-of-systems-1968/

“This year I learned how to learn,” wrote a first grader reflecting back on his school year. When asked to explain a bit more, he simply replied, “systems thinking allows me to put my thinking on paper where I can see it. When I can see my thinking, I can do more of it.”

What would happen if all of us actually did more thinking? There is certainly more to think about than ever before. The concept of a “knowledge development curve” is credited to Buckminster Fuller, who identified that up until 1900 knowledge doubled every century. By the mid-20th century, the doubling rate had increased to every 25 years. At the time of his writing he estimated information was doubling roughly every 13 months, In 2020 it was believed that human knowledge now doubles every 12-hours. This idea of an escalating rate of information makes sense given technology, access to information and the mechanisms we have for sharing information.

AI enhances the way we use available information. It makes me chuckle to hear my non-profit colleagues sheepishly admit that Claude produced a sophisticated work plan from their rapidly inputted, highly disjointed list of ideas, or that Chat GPT is able to create an eerily accurate bio for them by simply inputting their own name. AI is changing the way we interact with information. It increases our sense of efficiency. It is an easy way to access all our world’s rapidly growing body of knowledge. The people I talk with are both enamored by the possibilities and terrified by the repercussions of AI. Even as AI helps us summarize and generate ideas, systems thinking equips us to discern patterns, question assumptions, and consider consequences—skills that no algorithm can fully replace. AI has generative potential yet we still need to think…and like that first grader, to think more.

As we celebrate the 35th anniversary of the Waters Center, we pause to consider what are some of the ways we have delivered benefit to our clients and dare I say, to the world. Those benefits extend from classroom to boardroom, but with our roots firmly planted in education the number of stories that illustrate the ways systems thinking can impact learning are numerous. We, at the Waters Center, often use the mantra that we teach people how to think, not what to think.

As a rookie educator, I was given “programs” that promised to produce higher levels of thinking in my students. Those programs were filled with worksheets that can be likened to modern day game apps found on a tablet or cellphone. They were fun for certain types of learners, but beyond being a good time filler they didn’t really change anyone’s ability to think. However, as a more experienced teacher, when I discovered the Habits and tools of systems thinking, I saw students thinking more deeply, making connections between disparate pieces of information, and becoming much more aware of their own thinking. To use a bit of educator jargon, these students became more metacognitive, they could think about their own thinking and yes, they did a lot more thinking. Systems thinking provided concrete tools and Habits that I could offer students, which they could apply to whatever thinking challenge lay before them.

A multi-year triangulated research study conducted by the then Waters Foundation, from 2001-2006 identified five results of using systems thinking in the classroom.

Makes Thinking Visible. Students use systems thinking tools to clarify and visually represent their understanding of complex systems. This visual approach allows the students to interact with and explore thoughts, perceptions, and mental models with precision and clarity.

Making Connections. Systems thinking tools help students make connections between curricular areas and relevant life experiences.

Solving Problems. Students of all ages learn and independently use systems thinking problem-solving strategies.

Developing Readers and Writers. Systems thinking concepts and tools help students develop as readers and writers

Increasing Engagement .When using systems thinking concepts and tools, many students show increased motivation,and engagement.

You can access the full write up of that study here. This study is now almost 20 years old and while many things in education have changed significantly since then, including the advent of AI in everyday use, these five principles continue to be as true in classrooms today where the tools and Habits of Systems Thinking are integrated, as they were when the study was conducted.

A class of second graders engaged in a problem-based learning unit discovered the plight of the vaquita, a small porpoise species, that lives off the coast of Baja California. WIth a current population under ten, this species is critically endangered. This class of students used the visual tools to gather information, graphing patterns and trends of the vaquita population considering the events that led to their rapidly declining population, which causes students to eagerly await the vaquita population report published each year in June. They made a connection circle to identify causes of this steep decline in population. They used the Habits of a Systems Thinker to consider perspectives of different parts of the system, consequences of the species becoming extinct and accumulations necessary to create conditions for vaquitas to thrive. Rather than learning about this topic, students had the tools to delve deeply into understanding the problem and seeking solutions. The plight of the vaquitas is dire, but when these students share about the problem they do so with great hope, because they have tools to generate probable solutions to the challenge.

While offering hope was not one of the five major findings of the research study, it does happen repeatedly across classrooms intentionally integrating systems thinking and the importance of hope when facing challenges cannot be underestimated. When “more thinking” looks like rumination, stewing over problems, rehashing events, or focusing on undesired outcomes, it doesn’t produce hope. When thinkers have tools to put their thinking on paper, make novel connections and apply some tools for genuine problem solving, it can produce hope. Bringing clarity to a problem is an essential step for finding resolution.

The problem solving aspects of systems thinking in classrooms is very apparent when tackling big issues like an endangered species or something more specific to the school itself, like determining how to reduce noise in the cafeteria. AND systems thinking as a tool for problem solving is apparent in how students approach solving more traditional problems. For example, “word problems” or “story problems” in math can be more difficult for students than mathematical exercises that require straight calculation. By graphing the level of difficulty of various steps in solving word problems, requiring different mathematical operations and algorithms, students become more “metacognitive” about solving those problems. This increased understanding of their own thinking process enables students to more accurately solve the problems and builds their confidence because they focus on their strategies and their ability to be a mathematical thinker.

This same problem analysis is one of the ways systems thinking supports the development of literacy skills. This same analysis applied to solving math problems can be used to analyze a piece of written text. Thinking more about the text produces an ability to summarize, but more significantly an ability to see key themes and nuance. Like the student who after reading the story Goggles, by Jack Ezra Keats, confidently asserted that “action conquers fear.” She was attending to the fact clearly revealed on the behavior over time graph that every time the main character took action when faced with a threat from the bullies, he was more confident. Or the second grade class who had to leave unresolved the debate over whether the magic pebble in the the book Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, by William Steig, had more or less power when it was locked in the safe. Students had compelling arguments for both positions, so applying their problem solving skills, they decided the line of their behavior-over-time graph telling the story of power of the pebble would have to have go in both directions with their well written justification for each position.

Further in describing the impact of systems thinking on literacy development speaking from a myriad of interactions with students including teaching english composition at the college level, a systems thinking approach produces the most significant revision to writing that I ever witnessed among students. Using behavior-over-time graphs to map out the structure of a text a model text and then graphing the student writing visually illustrates where changes can be made to revise the text in ways that make significant improvement. It is another example of “more thinking” but with a specific method that goes beyond a reread and creates another perspective that is highly visible.

Finally, the fifth tenet of the research, systems thinking increases engagement. YES! Unequivocally for all the aforementioned reasons, when learners, of any age, do more meaningful thinking about something they care about, they will be more engaged. This is true not only of students in classrooms, but curious leaders problem solving with their team, executives in boardrooms working to improve fiscal outcomes or parents seeking ways to instill hope in their children. Systems thinking provides specific tools and strategies to do more thinking and when applied in work or in life the tools and Habits of systems thinking allow us not just to do “more thinking” but to think differently, with hope and confidence

The role of a leader can be daunting. As an elementary principal, I remember the feeling of dodging through a hailstorm, as matters of varying degrees of urgency and importance came hurtling at me from all directions. Okay, maybe that’s a bit of an exaggeration, but not much!

Today, the landscape of public education is shifting dramatically. Educators and school leaders are navigating a steady stream of challenges, from polarized public discourse to significant changes in policy and funding structures. These changes have left many hard-working, highly skilled practitioners second-guessing themselves or striving even harder to uphold their values, beliefs, and professional expertise.

How can those working in public education manage, sustain, and even thrive amid such uncertainty?

An Overview of How One Elementary School Introduced a Mindfulness Initiative

Almost a decade ago, well before the COVID-19 pandemic and today’s heightened political discourse surrounding education, my school made a decision to embrace mindfulness as part of our school improvement plan. The American Psychological Association defines mindfulness as "awareness of one’s internal states and surroundings." With this in mind, we set out to create a culture of presence, reflection, and regulation across our community.

We began by engaging the faculty in professional learning about mindfulness. We partnered with a local expert to learn about what mindfulness is, its benefits, how to practice it ourselves, and how to facilitate it with young children in a meaningful and manageable way.

Next, we introduced mindfulness into daily classroom routines. Using a research-based CASEL SELect program, we explicitly taught students about their brains and how they work. Teachers utilized a variety of mindfulness tools during transitions throughout their days to help students prepare for learning. For example, after recess, a teacher might dim the lights and allow students a few moments of mindful coloring at their seats before inviting them to the rug to begin the lesson. Others might begin by guiding students in a “Five-Finger Breathing” exercise, while some might choose to invite students to focus on the sound of a chime as it became fainter and silenced, signaling when they could no longer hear it. We also utilized storytelling - oral and children’s books - to convey the theme of mindfulness and presence.

Many classrooms established “mindful corners” where students could spend a few moments when they needed to reset or self-regulate. Though each such corner was unique, these were generally equipped with a cozy place to sit, as well as a variety of tools from which students could choose (stress balls, kinetic sand, glitter jars, etc.).

Beyond the classroom, we wove mindfulness into the rhythm of school life. As principal, as part of our morning video announcements, I proclaimed each Monday to be “Mindful Monday,” and guided the school in a brief mindful exercise to begin the week. We began our staff meetings and professional learning sessions with a “Mindful Moment.” Teachers took turns leading their colleagues in a brief exercise to help them transition from the frenetic pace of the school day into our time together as colleagues and adult learners.

Over time, many teachers began to cultivate a mindfulness practice of their own. One teacher opted to engage her fourth-grade students in a project to design and build a labyrinth at the school. This remains a lasting place where students and staff can pause to walk mindfully on the campus.

We also offered opportunities for parents/guardians and families to come to campus to learn about and practice mindfulness. Through parent/guardian education evenings and family “Be Kind to Your Mind” events, we equipped families to utilize the same strategies at home that students were learning in school.

Even though our explicit, school-wide focus on mindfulness waned over the years, these practices remain embedded in our culture. Teachers and students have continued to utilize mindfulness strategies during trying times in their personal lives, as well as when larger, more systemic challenges have surfaced.

Mindfulness Through the Lens of a Systems Thinker

As described above, at our school, we recognized that mindfulness could be a powerful tool to foster students’ self-regulation. What we didn’t fully anticipate was the ripple effect and the unintended benefit for the adults in our system.

As our mindfulness practices became embedded into the fabric of our school, I began to notice patterns that extended beyond individual strategies or isolated successes. The shifts we were seeing, in student behavior, staff resilience, and school culture reflected deeper systems at work. It was through this lens that I recognized clear connections to the Habits of a Systems Thinker, which helped us more fully describe and sustain the changes we were cultivating.

As you consider starting or deepening a mindfulness practice in your own context, the following Habits of a Systems Thinker may offer a helpful perspective, especially in today’s challenging climate.

Seeks to Understand THE BIG PICTURE - The public elementary school classroom can be seen as a microcosm of the larger society. We wanted students to have a sense of belonging to their classrooms and to the school, and to have regular opportunities to learn and develop academically, socially, emotionally, and physically. Teaching students how their brains worked, as well as how to self-regulate with various mindfulness strategies, equipped them with tools that would help them be successful in these endeavors.

Recognizes the Impact of TIME DELAYS When Exploring Cause and Effect Relationships - It has been almost ten years since we introduced mindfulness as a school-wide initiative. Some effects were quickly evident. For example, students could be seen choosing to spend a few moments in a mindful corner or selecting from a variety of breathing techniques (often with coaching) when engaged in a conflict with a peer. Other effects were evident after a time delay. For example, graduating high school seniors came back to campus years later and commented on the ongoing usefulness of mindfulness techniques they learned in elementary school, particularly during times of high stress and uncertainty, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

CONSIDERS Short-Term, Long-Term, and Unintended CONSEQUENCES of Actions - As described above, there were both short-term and long-term positive consequences (effects) of our actions. In addition, unfortunately, there were unintended negative consequences (effects) of our actions. A small number of families took exception to what their children were learning about mindfulness, as they believed it was being used to promote a religion. Most came to understand and support our efforts after individual conversations were held to explain and share more specifics of what we were doing and how we were doing it. However, at least one family chose to leave the school because of our mindfulness initiative.

Consider How MENTAL MODELS Affect Current Reality and the Future - It became evident that differences in some mental models about mindfulness were hindering our efforts to affect change for the entire school community, and we made some modifications because of this. For example, we had a staff member who was skilled at graphic design create a mandala (a geometric figure representing unity, harmony, and interconnectedness) using our school colors and mascot. After much consideration, though mandala designs had become popularized (used in gardens, fashion, pop culture, etc.), we opted to stop using the custom image because of their origin as a Buddhist devotional symbol.

Recognizes That a System’s STRUCTURE GENERATES ITS BEHAVIOR - From the various transition routines that teachers used to the weekly school-wide Mindful Monday exercise on the morning announcements, we built a number of structures that students (and staff) came to rely upon to develop mindfulness habits/practices.

Throughout this journey, mindfulness and systems thinking became steady anchors for our school community—structures we could lean on even as the broader environment shifted around us. As the winds of change in education have only grown stronger, these practices continue to offer a foundation for navigating uncertainty with resilience, clarity, and hope.

A Mounting Challenge

While these habits and practices offered us steady ground within our school, we were not insulated from the broader shifts affecting education across the country. As the years unfolded, external pressures on public education intensified, placing additional strain on the very people these systems rely on most-teachers and school leaders.

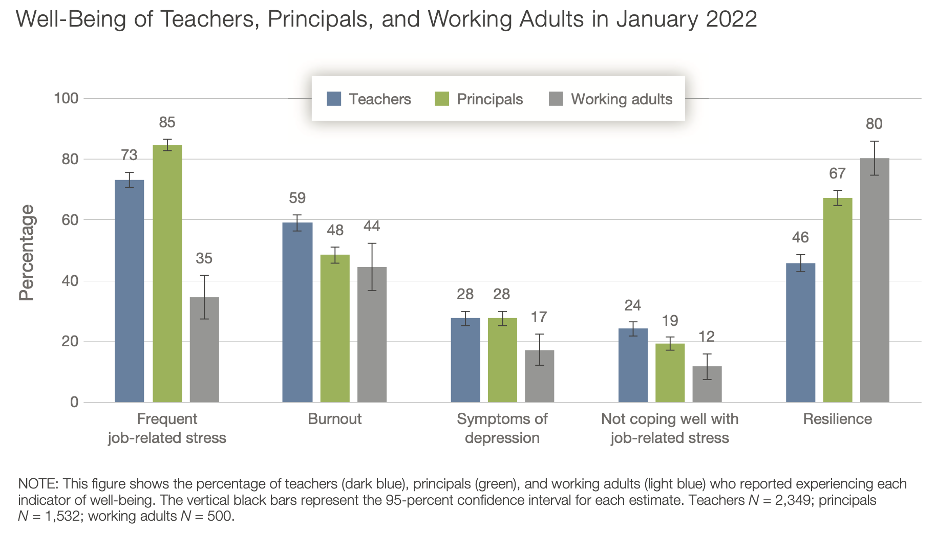

Teacher and principal well-being has been a concern for a long time. According to a January 2022 survey by the Rand Corporation, “Teachers and principals reported worse well-being than other working adults.” The following table is from their report:

This mounting pressure is not new, but it has become harder to ignore. While the data above reflects the post-pandemic climate, it does not take into consideration today’s polarized political climate. In early 2025, a series of federal policy changes—including executive orders and shifts in Department of Education priorities—signaled major disruptions for the public education system. These included actions related to curriculum oversight, department structure, and funding requirements. For many educators, these changes added new layers of uncertainty and concern.

How does one who works in public education manage amid such a maelstrom? While these national policy shifts introduced new challenges, they also reinforced the importance of the foundational practices we had already begun, especially mindfulness.

Navigating the Storm, One Step at a Time

In times like these, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed or powerless. But amidst the uncertainty, practices like mindfulness and systems thinking offer more than just tools - they offer perspective. They help us pause, re-center, and focus on what we can influence, even when so much feels out of our control.

Take a moment to consider how your understanding of the big picture of public education connects with what happens in your own school, classroom, or home. How can you maintain balance between the big picture and important details? What is in your sphere of influence today? What is not? What is in your sphere of influence over time?

Should you be interested in developing a mindfulness practice of your own, consider the patterns and structures that might support this. Know that developing new habits takes time and that you can anticipate time delays before seeing the results you desire. Are you open to short-term discomfort in exchange for long-term clarity, grounding, or gain?

And if the Habits of a Systems Thinker sparked your curiosity, there’s much more to explore. These habits—and the systems thinking tools that support them—can help you visualize ideas and relationships more clearly and act with greater intention.

If you want to explore how mindfulness and systems thinking might support your own practice or leadership, I’d love to be a part of that journey. Through Kimbo Coaching and Consulting, I offer coaching, consulting services, and capacity-building opportunities that help teams and individuals navigate complexity with greater clarity, calm, and connection.

No matter the weather around us, we can choose to lead from a place of steadiness within.

Today’s education challenges are more complex and dynamic than ever before, requiring education leaders and changemakers to rethink and reframe how they develop solutions. Systems thinking enables leaders to move beyond surface-level solutions to help drive deep change. However, change is not only the result of intentional actions. It is constantly unfolding all around us in ways that are far beyond our control. By adding a futures orientation to systems thinking, leaders can account for an ever-evolving external environment as they determine how to shift their systems in intentional ways.

Inbound and Outbound Change

The field of strategic foresight – a professional discipline that looks to the future to inform action today – describes two types of change, inbound and outbound. In Teaching about the Future, futurists Peter Bishop and Andy Hines (2012) describe inbound and outbound change as follows.

“Change comes from two sources – the world and us. Change from the world is Inbound because it comes at us. Change we produce ourselves is Outbound because it emanates from our actions into the world.”

Clearly, the boundaries are not absolute. Individuals and groups make choices that then have broad ripple effects, and large-scale social, economic and demographic shifts influence people’s decisions. However, treating inbound and outbound change as distinct categories can help changemakers balance their own sense of power and agency with many factors beyond their locus of control.

Leaders often base decisions on how a system behaves today without considering how inbound change might affect those plans over time. They tend to focus on present reality, past system behaviors and the outbound changes needed to shift current reality but overlook the inevitable inbound change that will most certainly shape the future. New realities, growing trends and unexpected disruptions all have the potential to introduce new opportunities, diminish the effectiveness of chosen actions or alter the depth of an action’s influence on the underlying system.

While the future will always remain uncertain, organizations can remain adaptable as conditions evolve if they examine and challenge assumptions about the future as part of their systems thinking practice.

Applying a Futures Orientation to a Systems Problem

In 2020, KnowledgeWorks published The Education Changemakers’ Guidebook to Systems Thinking, a resource designed to help educators, policymakers and communities apply systems thinking to create more student-centered learning environments. This publication is part of the organization’s broader thought leadership on education transformation, providing a structured approach meant to help leaders and education audiences understand challenges, identify leverage points and shape the future of learning.

The guidebook outlines three essential steps for effectively applying systems thinking in an education setting:

- Framing the Focus of a Systems Problem: Examining diverse perspectives within a system and defining the behaviors that we want to change

- Visualizing the Structure of a Systems Problem: Using systems thinking tools to visually depict system behaviors and create shared understanding about them and their interconnectedness

- Looking for Leverage to Create Change: Recognizing that all actions are not created equal and identifying high-impact actions, or leverage points, that might fundamentally shift the way a system works

From there, leaders can explore inbound change on the horizon and consider how they might want or need to adjust their plans.

Using Inbound Change to Check or Identify Leverage Points

Consider the very real issue of staffing shortages in schools. This is one of five key areas that are shaping how education operates today and will determine what unfolds for education systems and learners in the future.

Imagine that you are working on a staffing shortage problem in a school district. The shortage seems to be, at least in part, caused by teacher burnout. After framing the specific nature of the problem with a range of people who are part of the system – young people, families, educators, board members, counselors – and considering the many variables at work, you decide to request a new school counselor position. You believe that this position will both support student well-being and take pressure off teachers who are struggling to balance instructional workloads with students’ increasing social and emotional needs.

This robust process is necessary. But, from a futures-thinking perspective, it is not entirely sufficient. The next step would be to consider how broader shifts in society might demand that the school district think beyond this immediate solution to consider the evolving external factors that might influence its impact. The questions below illustrate some inbound changes that could influence how district leaders might decide to address their challenge.

How might the effects of accelerating technologies and climate change shift the timing, structure and delivery of learning?

How might increasing civic polarization affect the ways schools and districts approach students’ social and emotional well-being?

How might a changing economy affect both public and private funding for education?

How might shifting beliefs about the purpose of education, influenced by economic and social changes, change people’s expectations and priorities for the educational workforce?

These emerging shifts could reshape the staffing challenge in unexpected ways. They invite leaders to consider alternative approaches or possibilities such as those reflected in the questions below.

Will a traditional counselor role remain the most effective solution? Or could a newly imagined position better address the evolving needs of both educators and students?

What priorities for different constituent groups, such as parents or school board members, and possible political dynamics might emerge? How might those relationships and priorities change over time?

How might possible funding realities impact the feasibility of this decision? What types of circumstances would make the decision to hire a new role sustainable – or not?

What shifts in mental models might be necessary to ensure that the solution remained relevant as beliefs and circumstances shifted over time?

These questions do not have right and wrong answers. They may even highlight how much uncertainty about the future remains, underscoring the need for continued discussion and monitoring of the external environment. While seeking the new counselor position might still prove to be the best action for the school district to take at this time, having conversations about the changing landscape in which the system operates will surface new possibilities, including potential challenges and emerging opportunities, that could be worth watching.

The interconnected nature of systems means that there is no perfect answer and that every choice will have both intended and unintended consequences. Bringing systems thinking into the decision-making process provides a framework for navigating complexity. Adding long-term foresight to near-term decision-making processes can help education leaders take more informed and enduring action.

Systems Thinking Habits That Promote Futures Thinking

Systems thinking and futures thinking strengthen each other. Thinking about systems enables leaders to consider future possibilities with more rigor and depth. Considering future possibilities raises important questions about how systems behave and why and how they might change. The following Habits of a Systems Thinker are also habits of a futures thinker when approached and applied in certain ways. Considering the future-oriented dimensions of these habits can support and deepen both leaders’ systems thinking and their emerging futures thinking practices.

Seeks to understand the big picture: In systems thinking, seeing the big picture is about acknowledging the breadth and interconnection among today’s existing systems. In futures thinking, the big picture is about extending the time horizon and the long-term implications of today’s decisions.

Observes how elements within the system change over time: Systems thinkers look at how patterns of system behaviors have changed over time. Futures thinkers consider different patterns that might emerge and how system behavior could change in the future

Considers an issue fully and resists the urge to come to a quick conclusion: A system is never fully knowable because everyone within it sees things differently. That’s why visual tools in systems thinking are so valuable – they help create a shared understanding. The future is also uncertain, but instead of seeing that as a problem to solve, futures thinking encourages leaders to embrace uncertainty and consider all possibilities, which equips them to be ready for change and discover new opportunities.

Surfaces and tests assumptions: Understanding a system requires making assumptions because its components will never be fully transparent. Similarly, there are no facts about the future – only assumptions and possibilities. Bringing these assumptions to light from people involved in the system – how the system works, what they expect to happen and what they want to happen – can lead to powerful conversations about shaping change.

Systems thinkers are already well-primed to be futures thinkers. They are already deeply considering their own actions and how they might create meaningful outbound change. Considering inbound change and infusing a future orientation to well-established systems thinking habits can ensure that education leaders are prepared to lead through uncertainty and volatility and transform their systems in ways that create a better future for the people they serve.

Works Cited

Bishop, P. C., & Hines, A. (2012). Teaching about the future. Palgrave Macmillan.

KnowledgeWorks. (2020). The education changemakers’ guidebook to systems thinking. https://knowledgeworks.org/resources/education-changemakers-guidebook-systems-thinking/

"I understand systems thinking concepts, but how can I apply them to real life?"

Recently, a friend and former colleague asked me this question. To me, this person is a natural systems thinker, and I’ve seen them apply it with seemingly little effort in their work. However, as systems thinking has become a more central focus in their organization and their whole team has undergone systems thinking training, my friend expressed feeling stuck. They told me, “I love the ideas and the tools, but it isn’t always realistic to do a facilitation or map something. I want it to be an embedded part of our work, not something separate or occasional.”

We often encounter questions like these in our work at the Waters Center. And from our experience providing capacity-building, consulting, and coaching services across various industries, moving from understanding to consistent action is a common challenge. Systems thinking isn’t just about learning concepts—it’s about making it a natural part of how we think, work, and make decisions every day. It's about making it a habit.

And habits are something we are known for at the Waters Center, specifically the Habits of a Systems Thinker. The 14 Habits of a Systems Thinker help individuals understand how systems function and how actions influence outcomes over time. "The Habits" serve as guiding principles that encourage thoughtful questioning and provide a practical framework for applying systems thinking in real-world contexts. By practicing the Habits, systems thinking becomes less of an occasional practice and more of a natural way of engaging with the world.

At first, my friend thought they needed more tools—but what they really needed was a shift in mindset. And that’s where the Habits come in.

The Habits of a Systems Thinker

The first version of the Habits of a Systems Thinker were developed in 2006, building on over 15 years of systems thinking work in early childhood and K–12 education. Inspired by Art Costa and Bena Kallick’s Habits of Mind and shaped by collaboration with renowned systems thinkers like Linda Booth Sweeney, Donella Meadows, George Richardson, Barry Richmond, and Peter Senge, the Habits were designed to make systems thinking practical and accessible. Nearly 20 years later, they have found their way into classrooms, boardrooms, and organizations worldwide, helping people integrate systems thinking into their daily work and decision-making.

Each Habit represents a different way of seeing and engaging with the world. Some help us zoom out and get a more complete view, like "Seeks to Understand the Big Picture”, while others encourage us to pause and better understand the meaning we add, like “Surfaces and Tests Assumptions”. Some push us to consider potential ripple effects, like “Considers Short-Term, Long-Term, and Unintended Consequences of Actions,” while others help us find potential opportunities for meaningful change, like “Uses Understanding of System Structure to Identify Possible Leverage Actions.”

To help practice the Habits, each card has an illustration—like the relatable image of balancing a desire for a treat and the long-term dental implications on the “Recognizes the Impact of Time Delays When Exploring Cause-and-Effect Relationships” card. The cards also offer guiding questions on the back, inspired by real-world experiences across education, leadership, and organizational development. These questions prompt deeper reflection, helping users recognize when they are engaging in systems thinking and guiding them toward meaningful application in their unique contexts.

Making the Habits, Habits: Science-Backed Strategies

Now that we understand the power of habits, how do we actually make systems thinking second nature? The good news is that small, intentional shifts can create a significant impact over time.

Like other habits, behavioral science gives us useful clues about how we can make systems thinking part of how we move through the world. Research in neuroscience, such as Nicole Vignola’s Rewire (2024), highlights how intentional, repeated actions strengthen neural pathways, making new habits more automatic over time. The same principles apply to systems thinking—by deliberately engaging with the Habits of a Systems Thinker, we can rewire our brains to naturally approach problems through a systems lens.

Here are a few practical strategies to start building the Habits of a Systems Thinker into your daily life.

.png)

Start small and build momentum. We don’t have to overhaul the way we think all at once. When I’m coaching or working with clients on bringing the Habits into their daily practice, I ask, “What’s one Habit that already feels natural to you?” Starting from a place of familiarity makes it easier to build confidence and create meaningful change.

For example, if “Making Meaningful Connections Within and Between Systems” is already part of your thinking, you might naturally recognize relationships between different departments in your organization or see parallels between challenges in your field and broader societal patterns. To deepen this Habit, you could start mapping out those connections visually, engaging colleagues in discussions about cross-disciplinary links, or intentionally seeking out diverse industries or communities to compare how similar issues are addressed in different contexts.

Stack the Habits onto what you already do. One of the simplest ways to build a new habit is to anchor it to something you're already doing. Like drinking a glass of water after brushing your teeth to meet your hydration goals. BJ Fogg’s research (Tiny Habits, 2019) highlights this as habit stacking, a strategy where new behaviors are paired with existing routines, making them feel effortless over time. By linking systems thinking to daily actions, we make it a natural part of how we approach challenges and decisions.

For example, if you already have a journaling practice, you can incorporate systems thinking by adding a reflection question about how you applied a Habit that day. If your team meetings have a regular check-in question, you could use one from the back of a Habit card or craft a new question that encourages systems thinking in your discussions. By embedding the Habits into routines you already follow, systems thinking becomes a seamless part of how you work and think.

Create reminders and visual cues. Ever notice how setting your vitamins out reminds you to take them? Or how keeping a notepad nearby encourages you to jot down ideas as they come? These small environmental cues shape our behavior, often without us realizing it. That’s because visual cues prime our brains for action (Clear, 2018). The same principle applies to systems thinking—by making the Habits visible, they stay top of mind and become easier to integrate into daily routines.

Clear outlines the four laws of behavior change: make it obvious, make it attractive, make it easy, and make it satisfying. One way to make systems thinking habits more visible is by taping the Habits on the wall or designating a "Habit of the Week" and keeping that card with you or in a place you see often. You can also get creative—objects, images, or quotes can serve as reminders of key systems thinking principles. For example, placing a slinky on your desk can symbolize “Recognizing that a System’s Structure Generates Its Behavior.” Similarly, setting a rotating systems thinking quote on your phone’s lock screen can keep these ideas top of mind throughout the day.

Reflect and learn in real-time. Tracking progress and self-reflection can create a feedback loop that increases motivation and consistency (Clear, 2018). Research in cognitive science also suggests that reflection strengthens neural pathways by consolidating experiences, improving problem-solving, and fostering adaptability (Vignola, 2024). Reflection can take different forms, from structured practices like journaling to real-time moments of intentionality.

For example, after reading an email or text that may be activating, pause to "Surface and Test Assumptions" before responding and identify follow-up questions you could ask to get a more complete understanding. Beyond individual reflection, engaging in collaborative reflection can further deepen systems thinking. This could mean leveraging coaching sessions, creating a learning team at work to share insights, or partnering with an accountability buddy to exchange voice notes or messages about your reflections.

Practice in community. Bring others along on your systems thinking journey! Research from Tiny Habits (Fogg, 2019) emphasizes that behaviors are more likely to become habits when they are practiced in a supportive environment. Social reinforcement, accountability, and shared experiences make habit formation more sustainable. By embedding systems thinking into team discussions, collaborative problem-solving, and everyday interactions, individuals can reinforce their learning and deepen their application of the Habits of a Systems Thinker.

Making the Habits stick isn’t about adding extra work—it’s about rewiring the way we approach challenges and opportunities (Clear, 2018).

Your Systems Thinking Habit Challenge

Systems thinking becomes second nature through small, intentional shifts. It’s not about adding more to your plate—it’s about adjusting how you engage with challenges and decisions. By embedding systems thinking into everyday actions, building habits purposefully, and creating space for reflection, it transforms from an abstract concept into a practical, intuitive way of navigating complexity.

This week, choose one Habit of a Systems Thinker and commit to practicing it daily. Keep it visible, talk about it, and reflect on how it shifts your thinking. Maybe you start by asking one new systems thinking question in a meeting, or by pausing before making a decision to consider its long-term impact. Small steps, practiced consistently, lead to powerful change.

By embedding these Habits into our work and lives, we build the systems thinking capacity needed to make more thoughtful decisions and create lasting impact.

Which Habit will you focus on first?

Works Cited

Clear, J. (2018). Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. Avery.

Fogg, B. (2019). Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Vignola, N. (2024). Rewire: The Neuroscience of Changing Your Behavior and Achieving Your Goals. HarperCollins.